27 January 2006

Cézanne in Provence

The art Cézanne made in Provence, especially his last convulsive images of Mont Sainte-Victoire, ultimately shook painting to its core. It effectively destabilized centuries of representation to reach a deeper, fuller, nearly hallucinatory kind of realism. In the early 1900's, when Cézanne's paintings began to be known to younger artists like Braque, Picasso, Matisse and Mondrian, these works provided the foundations for Cubism and the multiple strands of early Modernism.

So writes critic Roberta Smith in the New York Times in her exceptionally cogent review of the exhibition "Cézanne in Provence" opening January 29 at the National Gallery of Art.

It was the landscape of Provence, more than anything else, that pushed Cézanne to make his particular changes. It prodded him to unhinge painting from conventional representation, to create breathing space between his brushstrokes and what they described. The proof is in the making. He brought a new equilibrium to painting's essential trifecta — the act of seeing, the psychic and physical process of painting, and the finished work — that gives the medium its novelistic richness and, even now, its firm grip on the imagination.

It is interesting to consider that although many of the artists that were affected by Cézanne's painting at the beginning of the twentieth century were political radicals who desired to overthrow the established institutions of Church and State and wanted a "modern" art that, in its rupture with the past, would express this radical agenda, Cézanne was conservative in his beliefs and a devout Catholic. Although it also happens, as his dealer Amrbroise Vollard tells us, that when the light was good for painting on Sundays "the curate had to get along without Cézanne."

I hope that everyone will make the effort to get to the exhibition. It should be more than worth it.

While you're there, be sure not to miss the exhibition of sculptures on tour from the Orasanmichele by Ghiberti, Nano di Banco and Verrochio, a rare opportunity to see monumental Florentine sculpture in the U.S.

21 January 2006

Ora et Labora

With apologies to WB+, I have borrowed the title of one of his recent posts, because in part, Whitehall has been the impetus for this post. (Be sure to read his follow-up post, too.)

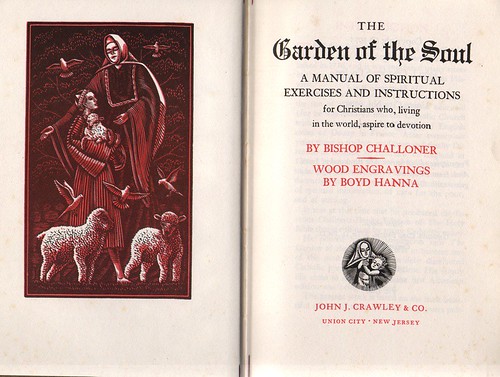

The notions of Ora (Prayer) and Labora (Work) have been very much on my mind lately, not least because I have been laboring in many areas lately toward many, but overlapping, ends. On the one hand, there is the on-going struggle to finish my M.A. thesis. Then there are my classes, my research assistantship, some service work for the university, my catechism class, dabbling with my paints, and lastly, this blog. And at the same time, I have endeavored to implement a greater degree of discipline in my prayer life, to which end The Garden of the Soul has been most helpful.

But they have also been on my mind because I have turned to painting icons, which being both paintings and devotional aids seem to be the epitome of ora et labora. I recently hunted up a quote by one of my all-time favorite artists, and devote Catholic, Balthasar Klossowski, known as Balthus. In his memoir, Balthus says,

I always begin a painting with a prayer, a ritual act that gives me a means to get across, to transcend myself. I firmly believe that painting is a way of prayer, a means of access to God.

Sometimes I've been reduced to tears, facing the challenges of a painting. Then I hear a godly voice speaking to me from within: "Hold on, resist!" It's a certain kind of grace, as in the libretto of Mozart's Magic Flute. These words, whenever I hear them, make me continue with my work. Follow the path until life is over.

What Balthus points out to us is not merely that the activity of painting can be an act of prayer. He also points us back to the divide that exists between the artist's intentions and the realization of the same. The work is a struggle towards an unattainable perfection. His Holiness, John Paul II, noted this condition in his 1999 Letter to Artists:

All artists experience the unbridgeable gap which lies between the work of their hands, however, successful it may be, and the dazzling perfection of the beauty glimpsed in the ardour of the creative moment: what they manage to express in their painting, their sculpture, their creating is not more than a glimmer of the splendour which flared for a moment before the eyes of their spirit.

The romantic concept of the artist as a tormented genius, which albeit needs nuancing and contextualizing, is not entirely off the mark. To make art—but I don't limit this strictly to art—is to enter into an uncertain half-way place between where one is and where one wants to get to, a place where the getting-to becomes more unlikely as one proceeds. It is the existential crisis tout court.

The crisis is insurmountable for anyone who does not have access to prayer. Because while art is a deliberate immersion in one's own perspective of the world, that is, one's subjectivity, prayer is the opposite. Prayer demands that one look at the world and oneself through the eyes of God. Prayer is the perfect complement for the work, because the work has usually only the glimmerings of the goal in mind and is entirely concerned with the striving, but without knowing how to get there. Prayer, on the other hand, has the goal so firmly in mind, but without the least concern for how the goal will be accomplished. It is the act of faith that the goal will be accomplished, and indeed has already been secured by divine intervention.

It must be this security which transforms the labora into ora, and vice versa. Because the work becomes a willingness to submit to the divine will and a way of communing with it; the work rests not only in the assurance of our being made complete in the image of Christ, but also a way of participating in that process as it unfolds.

I was going to write a short review of James Elkins' book What Painting Is, which I just finished, but I have decided against doing this because the premise of the book can be summed up fairly neatly: Elkins' sees alchemy and its belief that base substances (the prima materia, in alchemical-speak) can be transformed into the mythical, supernatural philosopher's stone as a metaphor for painting. In painting, it is colored muds that are miraculously transformed by the artist's labor into a transcendent object; through the process of painting they are made meaningful.

But perhaps this is taking the wrong end of the stick, or brush. Painting, and art in general, ought to be regarded as a metaphor for the very real work of transformation which the Holy Spirit is working out in the lives of every Christian. Like painting, it is slow, and works with imperfect, intractable elements made of mud. But unlike painting the end is certain.

20 January 2006

The BBC discusses Relativism

"Today, a particularly insidious obstacle to the task of educating is the massive presence in our society and culture of that relativism which, recognizing nothing as definitive, leaves as the ultimate criterion only the self with its desires. And under the semblance of freedom it becomes a prison for each one, for it separates people from one another, locking each person into his or her own "ego"." Pope Benedict XVI, in a speech given last June, showed that the issue of relativism is as contentious today as it was in Ancient Greece, when Plato took on the relativist stance of Protagoras.

Relativism is a school of philosophical thought which holds to the idea that there are no absolute truths. Instead, truth is situated within different frameworks of understanding that are governed by our history, culture and critical perspective.

Why has relativism so radically divided scholars and moral custodians over the centuries? How have its supporters answered to criticisms that it is inherently unethical? And if there are universal standards such as human rights, how do relativists defend culturally specific practices such as honour killings or female infanticide?

You can download or listen to the piece here. Thanks to a reader on Amy Welborn's blog.

Relativism is a school of philosophical thought which holds to the idea that there are no absolute truths. Instead, truth is situated within different frameworks of understanding that are governed by our history, culture and critical perspective.

Why has relativism so radically divided scholars and moral custodians over the centuries? How have its supporters answered to criticisms that it is inherently unethical? And if there are universal standards such as human rights, how do relativists defend culturally specific practices such as honour killings or female infanticide?

You can download or listen to the piece here. Thanks to a reader on Amy Welborn's blog.

16 January 2006

Some thoughts on two views of art history

In an earlier post, I put up a link to Roger Kimball's post reproducing the text of his talk at the Studio School on the New Criterion blog Armavirumque concerning his head-to-head with the art historian Michael Fried. Kimball's talk takes on the themes of his book—which I have not read but have been vaguely intending to, The Rape of the Masters—in which he lays out his criticisms of current academic art history, namely in its concern with "theory." Kimball concludes his post with this summation as to the role of the art critic:

In my view, it often happens that the most a critic can do is to remove the clutter impeding the direct enjoyment of art. True, that clutter sometimes includes the debris of ignorance or insensitivity, and in this respect art critics and art historians can provide useful guideposts that make it easier to see the work for what it is. But at bottom, their function is a humble one: to clear away the underbrush that obscures the first-hand apprehension of works of art.

Of course, this modest task has an ambitious corollary motive: namely, to help restore art to its proper place in the economy of cultural life: as a source of aesthetic delectation and spiritual refreshment.

This de-cluttering role is the approach that Kimball opposes to Prof. Michael Fried's "academic" art history which rather than clarify, supposedly obscures the work of art under a variety of interpretations—interpretations which expose supposed gender and power relationships or Freudian psychoanalytic undercurrents. Prof. Fried's art history isn't really concerned with anything so mundane—and perhaps more importantly—so subjective as appreciation, but instead is concerned with the arguably more "significant" task of interpretation.

I would like to agree with Mr. Kimball. Lord knows it would probably make my life somewhat simpler. But I find myself in the somewhat unfortunate position of agreeing neither with Mr. Kimball nor with Prof. Fried. Let me attempt, before proceeding further, to summarize what I perceive to be each their basic points of view: On the one hand is the "modernist" view held by Kimball, that the central goal of art history and criticism is apprecation and enjoyment. The connoisseur, that person of ultra-refined tastes and sensibilities leads you, the unrefined viewer, to see what he or she sees and thus identify that work of art with a certain degree of value and worth.

Fried takes the other, so-called "postmodernist" view wherein all systems of value are considered to be relative. Therefore, the art historian cannot possibly undertake the task of encouraging the viewer's appreciation. So instead it sticks to more, if not objective, at least impersonal task of interpreting what the work means. This method is not at all concerned whether or not an artist is "good" or "bad" but rather what the symbols in a given work of art means and where these symbols come from historically and how they relate to other works of art. This works on two levels: On one level the artist employs a set of signs within a work of art that allow it to be understood, for instance two intersecting perpendicular lines can make a cross can refer to aspects of Christian belief; and on the other level, the appearance of crosses in multiple works of art allow them to be grouped together and understood both in terms of similarity and difference.

If this were all that postmodernism was up to, it could hardly be supposed anyone would object. It's purpose is even more ostensibly more humble in so far as it proposes that it is more "scientific" than Kimball's. It is not concerned with saying which work of art has more value than another or even to help the viewer to evaluate (which, by the way, is what appreciate means), but merely to categorize and identify, to apply, so to speak, genus and species to works of art.

The connoisseur is almost always concerned with technique and manufacture; the hisorical critic with symbols and meaning, since they are more classifiable than the vagaries of paint application.

But the guise of science has allowed broad liberties to be taken within the field of art history. Often times, the task of interpretation, as Kimball rightly points out, becomes one of torturing works of art by casting them entirely in terms of psychoanalytic Freudianism. In fact, much of art history is steeped in psychoanalysis—Freudian, Jungian, and Lacanian seem to be the most popular—probably because both came of age at about the same time and both were concerned with the interpretation of symbols, and both, though circumscribed by subjectivity, like to posture as objective. Fried's approach is colored by psychoanalysis which allows him to make amazing intellectual leaps in his interpretations of painting and allow, him to, apparently, leave the work of art behind all together as he dives deep into the depths of the painter's psyche. It's all fine and well if you believe that psychoanalysis is true, but if you don't then the results of the psychoanalytic approach appear laughable at best, pernicious at worst. Perhaps the worst thing about the psychoanalytic approach is that it forecasts results. It assumes that whatever the work of art is presumably about, is in fact, a screen for another—usually seedier—meaning.

So, it's possible for the art historian to impose a false interpretation on a work of art. But this suggests that the only right interpretation of a work of art assumes that the work of art is a true and complete representation of the artist's intentions and that any symbolic content ought to be taken at more or less face value. If, then, a work of art becomes an accretion of collected meaning as the Mona Lisa has become, then the work of the art historian is to exhume its "original" meaning.

But this is problematic too. The original meaning and the intention of the artist are, practically speaking, just as speculative as Fried's psychoanalytical interpretations. But more significantly, the artist's intentions even when known and understood often don't account for the obvious fact that works of art partake of systematic conventions, perpetuating received ideas about what art is and how it functions. Sometimes these conventions, which are powerful forces sometimes inverted or parodied but rarely if ever absent, are at work despite the artist's stated intentions. Sometimes, the artist's intentions and the conventions of art exist butted up one against the other within the work of art in conflict with one another. In those cases, the work of the art historian is to uncover this state of affairs and present it to the audience. In this case, it would be intellectualy dishonest and wrong to merely "unclutter" the work of art for the viewer, when what it needs instead is precisely a good cluttering up! The temptation exists, doubtless, as Fried is testimony to, find and present such clutter in every work of art. But perhaps it is not wrong to say it is there, when really, the complex of events which produce works of art preclude the romanticized economy of the artist in his or her studio engaged in "self-expression."

Because I do not believe in psychoanalysis, I can't really agree with the intellectual assumptions which underpin most of the thinking of contemporary art historians and cultural critics. But because, works of art are more complex than mere objects of aesthetic enjoyment, I can't really take the modernist-connoisseurship position either. More on all this as it develops.

The Garden of the Soul

Because I was in Portsmouth over the weekend, I went to the Episcopal church down the street on Sunday. One of the things that I must say I will miss tremendously once I have finished converting to Roman Catholicism is Rite I in the Book of Common Prayer. The fact that, as far as I know, there doesn't seem to be anything really equivalent to it in the Catholic church has always been a bit of a mystery to me and a source of aggravation, since the BCP is both an exceptional piece of literature and a convenient devotional guide.

Anyway, all that has changed now. One of the other reasons that I go to this particular Episcopal church when I am in town is that one of my very good friends attends there as well: George Tussing. George is without doubt one of the most important and influential people in my life. If there is anyone I have to thank (or to blame) for my decision to go in for art history, it is him, since he was my very first art history teacher and one of the few who really understands and cares about art (and is himself an artist). So when I saw George at church on Sunday we got to talking about the Episcopal church and my conversion and he told me that he had this book he wanted to give me.

The book, as it turns out, is this book, The Garden of the Soul, by an English bishop named Challoner and originally published in America in 1776. It's a very beautiful book, with morning and evening devotions, prayers, supplications, hymns, the ordinary of the mass and a bunch of other stuff. It's even illustrated with woodcuts (take that, BCP!) Needless to say, I am extremely excited about it. I'll have to put it next to my bed, so that I don't forget to use it.

14 January 2006

Is there even such a thing as "Protestant" art?

Friend MM has posted an interesting observation about the lack of depictions of Christ, especially crucified, in Protestant churches. In my own experience they are becoming rarer and rarer. You can view my comments there and leave some of your own.

12 January 2006

Something worth watching

I started watching the TV show "Monk" because there was a free promotional episode on iTunes. If you have not seen this show, I highly recommend it. It stars Tony Shaloub as the obsessive-compulsive private investigator, Adrian Monk, and Traylor Howard as his assistant, Natalie Treeger. The basic premise is that Monk's neuroses, which inhibit him in about every other area of his life, give him an accute attention to detail, allowing him to detect clues that other people miss. But the show is extremely enjoyable, funny, well-written and extremely gentle and warm in its portrayal of its characters and their relationships. It's even won a bunch of awards. It airs Friday nights at 10pm on the USA network (of all places).

Charlie Finch on the new religion, Art

My friend ES sent me the link to this article on Artnet yesterday, concerning the quasi-religious aspects of contemporary art. Truth be told, I am pretty out of the loop in terms of the contemporary art scene. I have caught up with art history about as far as the '60s and after that things get pretty blurry (perhaps, then Donald Kuspit's forthcoming book, A Critical History of 20th-Century Art will fill a void, who knows). Anyway, Charlie Finch's article is interesting and worth a scan, which doesn't take more than a few moments.

The more important question, however, is is art a substitute religion? As someone aligned with a full-fledged mainstream, tax-exempt religion, I hardly think so, or at least, it is not a substitute religion any more than a host of other substitutes, like politics or money or popular culture.

I suppose this is the logical result of a conceptual shift in terms of what art is that happenedhttp://www.blogger.com/img/gl.link.gif around the turn of the last century. Art and aesthetics were seen as a path to the transcendent apart from any other mediating body. Or at least that's what Kuspit seems to be suggesting (see above link). There are certainly people, who exhausted of the scientific positivism and materialism of the nineteenth century sought refuge in the subjectivities and vagaries of art. But that doesn't really account for the apparent religious response to art today. Not altogether, anyway.

I guess your response to this situation depends on whether or not you think it is a problem and if so, what the solution might be. On different days I feel differently about it, ranging from deep concern to benign unconcern to total indifference. If you do think that there is a problem, then the only solution to offer is to propose that art be put in the employ of interests outside itself. Art would have to be commissioned and useful, e.g. portrait commissions, religious pictures, etc. Abstract art would probably become solely the province of corporations seeking non-objective, and therefore not objectionable, wall decorations.

Honestly, this is an impossible alternative. Art will remain, as far as I can tell, insular and self-reflexive for the time being. Although, there will always be dissenters.

The more important question, however, is is art a substitute religion? As someone aligned with a full-fledged mainstream, tax-exempt religion, I hardly think so, or at least, it is not a substitute religion any more than a host of other substitutes, like politics or money or popular culture.

I suppose this is the logical result of a conceptual shift in terms of what art is that happenedhttp://www.blogger.com/img/gl.link.gif around the turn of the last century. Art and aesthetics were seen as a path to the transcendent apart from any other mediating body. Or at least that's what Kuspit seems to be suggesting (see above link). There are certainly people, who exhausted of the scientific positivism and materialism of the nineteenth century sought refuge in the subjectivities and vagaries of art. But that doesn't really account for the apparent religious response to art today. Not altogether, anyway.

I guess your response to this situation depends on whether or not you think it is a problem and if so, what the solution might be. On different days I feel differently about it, ranging from deep concern to benign unconcern to total indifference. If you do think that there is a problem, then the only solution to offer is to propose that art be put in the employ of interests outside itself. Art would have to be commissioned and useful, e.g. portrait commissions, religious pictures, etc. Abstract art would probably become solely the province of corporations seeking non-objective, and therefore not objectionable, wall decorations.

Honestly, this is an impossible alternative. Art will remain, as far as I can tell, insular and self-reflexive for the time being. Although, there will always be dissenters.

07 January 2006

Courbet, Modernism and Postmodernism

Roger Kimball has posted the text of a talk given at the Studio School on Armavirumquein which he lays out his critique of current academic, postmodernist art history. It's lengthy but worth the read, I'd say. I have my own set of thoughts on the matter which once I have sorted out I hope to get posted.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)